Giving sight to machines

Making sense of pictures, videos and objects is no simple feat for machines, but these innovations are making it possible.

Humans are visual creatures—more than fifty percent of the human brain is directly or indirectly involved in processing visual information. While often taken for granted, our sense of sight influences how we make decisions, helps us navigate complex three-dimensional landscapes and allows us to complete tasks efficiently. Now imagine if machines could see as well as we do—how much more capable might they become?

For over five decades, scientists have been exploring various methods to grant machines sight. This entails not only developing better hardware for image or video capture, but also creating the software for identifying and interpreting key features of pictures and objects.

Today, several consumer devices are already capable of recognising faces or automatically captioning photographs, and doctors can now rely on computer vision tools to better diagnose diseases. Meanwhile, in factories, robotic arms need no longer be hard-coded with instructions to perform every action—they can observe, plan and react accordingly.

In this month’s TechOffers, we highlight three instances where ‘seeing’ machines could help organisations raise productivity and even save lives.

Clarity in the crosshairs

Not every image is taken perfectly—sometimes, the lighting is poor, or haze, smoke, dust or fog may obscure key features in a picture. To overcome these ‘visual barriers’, an image processing algorithm has been developed to increase the visibility of subsurface details. The algorithm can be embedded into the cameras of drones, underwater remote-controlled vehicles and even satellites or planetary rovers to enhance the quality of image capture and analysis.

Medical diagnostics also stand to gain from sophisticated image processing algorithms. For example, an advanced dermatology imaging software is now available to help clinicians look beneath the skin surface—in real time and under normal light—for early signs of conditions such as psoriasis or vitiligo. The software can also distinguish between skin lesions that appear the same to the human eye but actually have very different root causes, thereby improving the accuracy of diagnosis.

Evaluating emotions

Taking image processing one step further, a spin-off company from the Advanced Digital Sciences Centre (ADSC) in Singapore, has developed artificial intelligence (AI) that can read human emotions with high precision. Based on real-time images or video feeds, the AI analyses facial features and is able to conclude whether a person is happy, angry or sad, among other emotions. Importantly, the AI algorithm is not computationally intensive, which makes it suitable for deployment on a wide range of computer operating systems and devices, even mobile platforms.

By automatically assessing emotions, marketers could develop more targeted and effective campaigns based on their audience’s visceral responses to advertisements. The hospitality industry could also measure customer satisfaction based on facial expressions rather than responses on feedback forms. Furthermore, social robots, especially those intended as companions for the lonely elderly in their homes, need to be able to sense and respond to human emotional states. This technology could therefore be immensely useful wherever human emotions need to be identified and analysed for actionable insights.

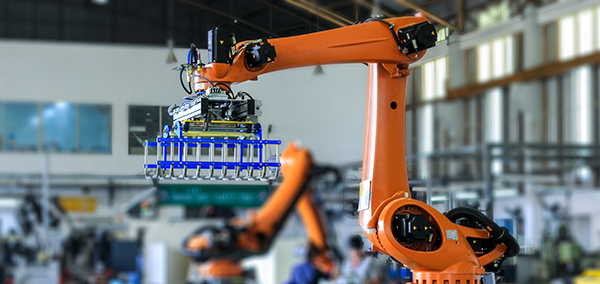

Setting sights on a whole new dimension

Setting sights on a whole new dimension

More complex than analysing pictures and videos—all of which are two-dimensional—is making sense of an object, which exists in three dimensions (3D). Depending on how a 3D object rests on a surface, it can appear very different when viewed from different angles, and this presents challenges to autonomous production systems.

To overcome this limitation, a technology provider has created a 3D vision system consisting of a 3D scanner and a software package for industrial robots. Relying on laser projection to obtain a virtual representation of a 3D object, the scanner boasts a deep field of view, subpixel accuracy and low noise. Using the 3D information, the system then assigns grip points and alternative grip points on objects, allowing for their rapid and precise manipulation by robotic arms.

This technology is not restricted to the factory line but could also be applied in other contexts where 3D information is critical, such as in autonomous vehicles and augmented reality apps.